Last month, Walmart announced it would raise its minimum wage to $10 by April 2016. The announcement follows years of organizing and advocacy by employees demanding the retail giant improve pay and working conditions in its more than 5,100 stores. But Walmart’s promise of $10 falls well short of what the highly profitable company can afford to pay its workers, and well short of the $15 these workers are rightly demanding. Walmart’s announcement also fails to give a guarantee of the full-time work hours employees want and need to provide stable lives for their families.

Walmart is far from alone in its failure to provide more work hours to employees who want them. (These employees are commonly termed as working “part time involuntarily.”) A recent study of a national sample of 26-to-32-year-olds working in a range of occupations found significant fluctuations in work hours and an especially low average number of minimum weekly hours among people working part time.

Given that Walmart sets standards in the retail sector, the company’s announcement has promptedgreater attention to the problem of involuntary part-time work in the retail industry. We took a look at the most recent labor force data available on involuntary part-time work in the retail industry, and our findings suggest that inadequate work schedules may be an especially significant problem for adult women and women of color employed in retail.

“Involuntarily part time employed” is defined in the Current Population Survey—the primary source of monthly labor force statistics—as (1) anyone who usually works full time, but who reports working fewer than 35 hours because of slack work, and (2) workers who want to work full time but who usually work part time because of slack work or because it’s the only job they could find. (Note that this measure doesn’t capture workers who voluntarily work part time but are scheduled for fewer hours in a week than they want.)

We limit our analysis to 18-to-64-year-olds, as they are more likely than teenagers or workers approaching traditional retirement age to want and be available for full-time work.

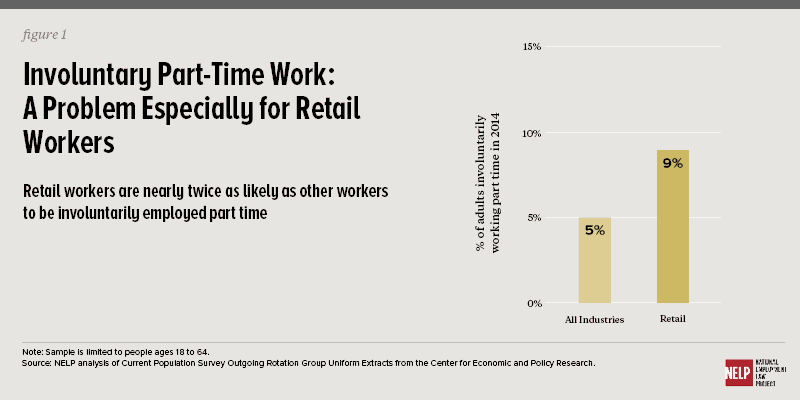

First, we look at the share of employed adults in all industries and in retail trade who work part time even though they would rather work full time. As Figure 1 shows, 9 percent of adult retail workers involuntarily worked part time in 2014, compared with just 5 percent of all working adults.

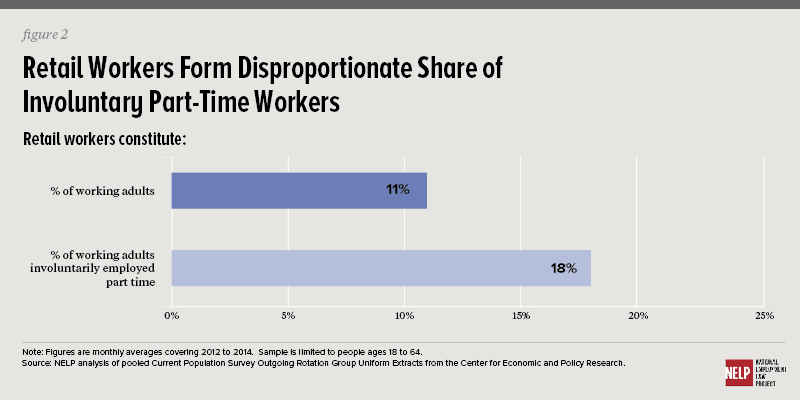

Next, we look at how retail workers and certain demographic groups within retail may experience disproportionately high rates of involuntary part-time employment relative to their share of all working people. To ensure a large-enough sample for our analysis, we pool the last three years of data. The results can be understood as monthly averages for 2012 to 2014.

Consistent with results in Figure 1, Figure 2 shows that retail workers make up 11 percent of working adults, but 18 percent of adults involuntarily working part time.

Next, we find women make up about 48 percent of adults working in retail, but 58 percent of adults in retail involuntarily working part time (Figure 3). This imbalance is significant given that women make up 47 percent of adults working in all industries, and 51 percent who involuntarily work part time, a difference of just four percentage points. So while adult women in general don’t experience a highly disproportionate rate of involuntary part-time employment, women in retail do.

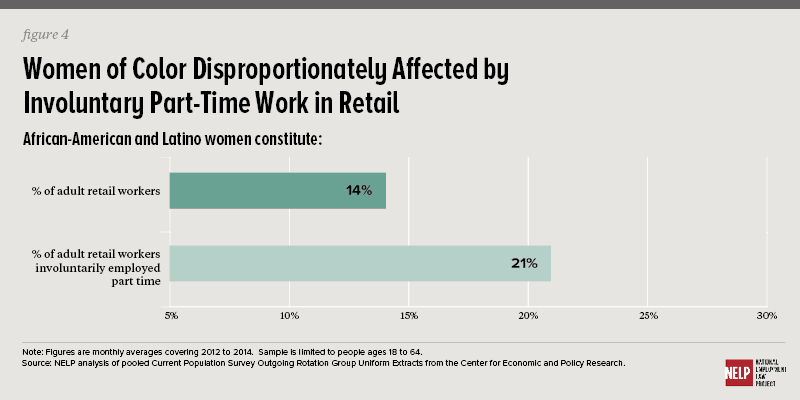

Finally, Figure 4 shows that African-American and Latino women make up 14 percent of adult retail workers, but 21 percent of adults in retail who involuntarily work part time. And African-American and Latino women are a slightly larger share of involuntary part-time workers in retail than in the employed workforce overall (21% compared to 19%).

These findings are a snapshot, but they suggest that calls for greater work hours by Walmart employees are well founded. The share of retail workers with involuntary part-time schedules is almost twice as large as the share of all employed workers. Further, the problem of inadequate work schedules in the retail industry may be especially significant for adult women and women workers of color. As the call for more stable and adequate schedules grows louder, NELP will continue researching trends on this important issue for lower-wage workers.