How Mandatory Arbitration Weakens Workplace Laws and Lets Employers Off the Hook

Mandatory arbitration clauses—fine print contract terms that bar lawsuits—are everywhere. Once limited to negotiated agreements between corporations with comparable bargaining power, arbitration provisions can now be found in the terms of service for widely-used, take-it-or-leave-it consumer and employment contracts. Most employers in the U.S. now require employees to accept a mandatory arbitration clause—waiving their right to sue in court as a condition of work.

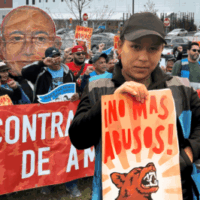

Arbitration clauses are often buried in the fine print of one-sided employment contracts that businesses impose, and that workers have no power to contest. Workers must either accept the contract as is or reject the job. Cashiers at Walmart, warehouse workers at Amazon, and drivers for Uber all must accept a contract that prohibits them from bringing a lawsuit for violations of their rights except through final and binding arbitration.

Mandatory arbitration is dramatically limiting workers’ access to courts and allowing employers to circumvent the judicial system. Since the 1990s, courts have consistently enforced arbitration clauses in employment contracts and employers have responded by increasingly using them. Currently, more than half of all non-union private sector employers bind employees to mandatory arbitration, and 60 million workers in the U.S. no longer have access to the courts to vindicate their workplace rights.[1]

This fact sheet addresses the following frequently asked questions about mandatory arbitration:

- What are arbitration clauses?

- How do arbitration clauses work in practice?

- Do workers recover as much in arbitration as they do in court?

- How does mandatory arbitration impact workers’ power to hold employers accountable?

- Does arbitration force law-breaking employers to change their behavior?

- Have employers always used mandatory arbitration provisions to avoid accountability, or is this new?

- Are these clauses always enforceable in court?

- Isn’t arbitration an easier and more efficient way to resolve legal disputes than going to court?

- What can we do about forced arbitration?

What are arbitration clauses?

An arbitration clause is part of a contract that forbids either of the parties from litigating a claim—i.e., bringing a lawsuit against the other in court. Instead, they “agree” to bring disputes to a private arbitration process, overseen by an arbitrator.

While some arbitration clauses may just be one sentence long, many employers are using longer and increasingly complex language in these clauses. A 2024 UberEATS’ terms of service update, for example, includes an arbitration clause that is fourteen pages long.

An example of a mandatory arbitration clause UberEATS imposes on its delivery workers:

“This Arbitration Provision requires all such claims to be resolved only by an arbitrator through final and binding individual arbitration and not by way of court or jury trial.”

Most employers also include class-action waivers with their arbitration provisions, which prohibit workers from bringing any claims against their employer on a class or collective basis. If an underpaid worker wants to join with their coworkers to sue their employer for wage theft under the Fair Labor Standards Act, for example, they cannot. Those claims must be brought on an individual basis and cannot go to court. The same is true for discrimination under Title VII and other laws where workers might be better positioned to demand accountability by acting as a group.

How do arbitration clauses work in practice?

If a worker suffers a violation of workplace rights—such as racial discrimination, sexual harassment, or wage theft—they generally have the right to go to court to resolve their claims. However, if their employment contract contained an arbitration clause, the worker likely waived that right, and the employer may compel arbitration and dismiss the lawsuit. Regardless of the nature of the legal violations involved, the worker will be required to proceed through arbitration, often individually.[2]

An arbitrator’s judgment is generally treated as final and binding, meaning workers cannot appeal the judgment to a state or federal court. The award is also private. Unlike judicial decisions, arbitration awards are not published and do not create any binding rules for future courts or arbitrators to follow. These clauses keep workplace abuse out of the public eye, closing the courthouse doors and eliminating the power of juries or judges to stop, and to publicly rectify, violations of workers’ rights.

Do workers recover as much in arbitration as they do in court?

No. Workers tend to recover much less when they are forced into arbitration than when they litigate their claims in court. The potential to present claims to a jury, along with well-established rules of procedure, generally make the courtroom a better forum for workers.

Workers are twice as likely to prevail, and take home an average of fifteen times more, when they proceed in court than when they are forced into arbitration.

One study found workers are almost twice as likely to prevail in federal court than in arbitration, and that workers who won took home a cash judgment fifteen times greater in court than in arbitration.[3] In federal court, plaintiff employees won 36.4 percent of the time with an average award of $336,291. In arbitration, they won only 18.9 percent of the time with an average award of $21,871.[4] Another study of claims brought by misclassified janitors against their employer found that those forced to arbitrate recovered only a few thousand dollars, in comparison to those able to proceed in court, who recovered upwards of $20,000.[5] Workers forced to arbitrate their claims face the prospect of getting only a fraction of the relief that might have been available to them in court.

How does mandatory arbitration impact workers’ power to hold employers accountable?

Many workplace claims are for relatively small individual dollar amounts, and they may result from systemic employer policies that affect the entire workforce, like an illegal hiring policy or independent contractor misclassification.[6] Such claims are best suited for class or collective actions, where a group of workers can seek redress for illegal behavior affecting them all. However, employers that mandate arbitration often include class-action waivers in their employment contracts. This prevents workers from litigating their cases jointly, and instead requires them each to proceed with their relatively small individual claims through arbitration. Courts have even forced workers into individual arbitration when they allege violations of the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, which has its own statutory mechanism specifically enabling workers to bring claims as a collective.

Workers who have been wronged cannot join together to bring their claims, and for most, that means they cannot afford to bring their claims at all. The cost to workplace enforcement is stark—by one estimate, under two percent of workers with employment claims that would otherwise be litigated in court are ever brought to an arbitrator.[7]

Does arbitration force law-breaking employers to change their behavior?

No, mandatory arbitration allows employers to keep on breaking the law. Successful arbitration may result in an award of backpay or damages for an individual worker, but arbitrators cannot award injunctive relief—i.e., they cannot order the employer to change their practices going forward. As a result, private arbitration awards not only allow companies to keep their law-breaking activity secret, but they also allow companies to continue violating the law as long as they pay the relatively minimal cost of any individual arbitration awards.

Because arbitration awards are private and arbitrators lack power to order ongoing compliance, they cannot produce lasting solutions that force employers to change their behavior. As a result, illegal employer practices, like independent contractor misclassification, continue unabated until a court—not an arbitrator—rules them to be illegal.[8]

Have employers always used mandatory arbitration provisions to avoid accountability, or is this new?

Mandatory arbitration in the workplace is relatively new and has never been more widespread than it is right now. Arbitration agreements first became prevalent in the early twentieth century, as large corporations looked to alternative forms of dispute resolution to avoid the costs of going to court.[9] In 1925, Congress passed the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) to allow companies to agree to arbitrate contract disputes.

The FAA is still the main federal law that governs arbitration agreements. By its own terms, the FAA applies only to contractual disputes, and for many years arbitration was a procedure limited to contractual disputes between large corporate actors.[10] Starting in the 1980s, however, employers began inserting these clauses in employment contracts to cut compliance costs and avoid class-action lawsuits. In a series of decisions beginning in the 1980s, the U.S. Supreme Court expanded the reach of the FAA, requiring enforcement of arbitration agreements to statutory claims,[11] including in employment contracts.[12] Now, even when the provisions are part of take-it-or-leave-it employment contracts between parties with different levels of bargaining power, like a large corporate employer and an individual worker, they are consistently upheld. As a result, the share of workers subject to mandatory arbitration rose from just over 2 percent in 1992 to almost a quarter in the early 2000s, and has since more than doubled to over 55 percent.[13]

Are these clauses always enforceable in court?

Arbitration agreements in employment contracts for underpaid workers across the economy are routinely enforced. In 2023 and 2024, workers at Walmart,[14] Amazon,[15] DoorDash,[16] Instacart,[17] Uber,[18] and many other major companies have all been forced to arbitrate their workplace claims. Workers in restaurants, warehouses, and major banks are increasingly likely to have their claims sent to arbitration.[19]

Under the Supreme Court’s pro-arbitration rulings, it is difficult for state legislatures and courts to give workers a path around arbitration into state court.[20] The Court has also read the FAA’s main exemption—which applies to workers in “interstate commerce”—narrowly, only excluding those who do interstate transportation work from coverage.[21] Most railroad workers, truckers, airline workers, and a handful of others, can avoid arbitration and take their employers to court. But for most workers in the U.S., the Supreme Court’s recent decisions have shut the courthouse doors, tipping the scales further in favor of corporate power.

Isn’t arbitration an easier and more efficient way to resolve legal disputes than going to court?

In certain contexts, alternative forms of dispute resolution offer some advantages over going to court. Where two parties with similar bargaining power come to a negotiated agreement to arbitrate their disputes, arbitration can mean avoiding some of the legal fees that come with going to court. But for workplace disputes, the effect of arbitration is one-sided. Workers cannot take advantage of the cost-savings and efficiencies of litigating their claims as a class or collective and sharing the associated legal fees. Instead, an individual worker seeking $2,000 in backpay might face the prospect of paying $100,000 in arbitration fees, attorney’s fees, and expert witness fees.[22] They stand less chance of winning, win much less if they do win, and pay substantial fees to fund the arbitration process.

What can we do about forced arbitration?

Change Federal Law

The FAA can be amended or repealed by Congress. In recent years, Democratic lawmakers have introduced legislation, including the FAIR Act, that would exempt most consumer and employment contracts from the FAA.[23] Lawmakers serious about restoring workers’ rights to litigate should support this kind of legislation.

Change State Law

State law alone can’t solve the problem of forced arbitration, because the U.S. Supreme Court has found most state efforts to circumvent the FAA to be “preempted.”[24] But many states have laws similar to the FAA that pose an additional obstacle for workers trying to litigate their workplace claims. Repealing these harmful laws is a good first step. State laws can also create additional pathways to court for workers bound by arbitration clauses, such as third-party enforcement provisions, and “qui tam” statutes like California’s PAGA, and New York’s EMPIRE Act.[25]

Reform the Supreme Court

The outsized importance of today’s FAA is the product of 35 years of anti-worker jurisprudence from the Supreme Court. But the meaning of the FAA continues to be litigated, and the Court’s decisions can be reversed—if we have a more democratically responsive Supreme Court.

Join a Union

Unionized workplaces are governed by collective bargaining agreements, not individual employment contracts, and workers who suffer legal violations can turn to their union for support, rather than being left to pursue their claims alone in arbitration.

Endnotes

[1] Alexander J.S. Colvin, The Growing Use of Mandatory Arbitration, Econ. Pol’y Inst. (Sept. 27, 2021).

[2] A 2022 amendment to federal law created an exemption for sexual assault claims, which can now be litigated even where the victim workers is bound by an arbitration clause.

[3] Alexander J.S. Colvin & Kelly Pike, The Impact of Case and Arbitrator Characteristics on Employment Arbitration Outcomes 17 (June 2012) (presented at the annual meeting of the National Academy of Arbitrators, Minneapolis, Minn.).

[4] Id. In state court, the outcomes for workers are more favorable: they won 57 percent of the time, taking home an average of $462,307.

[5] Carmen Comsti, A Metamorphosis: How Forced Arbitration Arrived in the Workplace, 35 Berkeley J. of Employment & Labor L. 6 (2014).

[6] No Due Process, No Rights: How Forced Arbitration Enables Misclassification in the Gig Economy, National Institute for Workers’ Rights (Aug. 1, 2021), https://niwr.org/2021/08/11/no-due-process-no-rights/.

[7] Cynthia Estlund, The Black Hole of Mandatory Arbitration, 96 N.C.L. Rev. 679, 696 (2019).

[8] See, e.g., Independent Contractor Misclassification Imposes Huge Costs on Workers and Federal and State Treasuries, NELP (Oct. 26, 2020).

[9] Margaret Moses, Arbitration of Worker Contracts: New Prime’s Proper Statutory Interpretation of the 1925 Federal Arbitration Act, 21 Cardozo J. of Conflict Resolution 415 (2020).

[10] The text of the FAA declares that written provisions in a contract “to settle by arbitration a controversy thereafter arising out of such contract” are “valid, irrevocable, and enforceable.” 9 U.S.C. § 2.

[11] See Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991).

[12] Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Adams, 532 U.S. 105 (2001).

[13] Alexander J.S. Colvin, The Growing Use of Mandatory Arbitration, Econ. Pol’y Inst., at 1 (Sept. 27, 2021).

[14] Walz v. Walmart, Inc., No. 23-cv-06083 (W.D. Wash. Jun. 6, 2024).

[15] Rittmann et al. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 16-cv-01554 (W.D. Wash. 2024).

[16] Silva v. DoorDash, Inc., No. 23-cv-00104 (M.D. Fla. 2023).

[17] Chambers v. Maplebear, Inc. (d/b/a Instacart), No. 21-cv-7114 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 27, 2024).

[18] Aleksanian v. Uber Techs. Inc., No. 22-98-cv (2d Cir. Nov. 14, 2023).

[19] See, e.g., Gonzalez v. Cheesecake Factory Restaurant, No. 21-cv-5018 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 6, 2024); Burgos v. Citibank, No. 23-cv-01907 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 19, 2024).

[20] AT&T Mobility, LLC v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011).

[21] Bissonnette v. LePage Bakeries, LLC, 601 U.S. __ (2024); see also, e.g., Imre Szalai, A New Legal Framework for Employee and Consumer Arbitration Agreements, 19 Cardozo J. Conflict Resol. 653 (2018) (“Thus, at the time of the FAA’s enactment, and for several decades thereafter, the FAA was read to not apply to employment relationships.”).

[22] See, e.g., Katherine V.W. Stone & Alexander J.S. Colvin, The Arbitration Epidemic: Mandatory Arbitration Deprives Workers and Consumers of their Rights, Econ. Pol’y Inst. (Dec. 7, 2015) (describing the cost structure of individual arbitration in a recent cast).

[23] H.R. 1525: FAIR Act of 2023, 118th Cong. (2023-2024).

[24] See, e.g., AT&T Mobility, LLC v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011).

[25] Legislative Memo: EMPIRE Worker Protection Act, N.Y. Civ. Liberties Union (May 27, 2022), https://www.nyclu.org/resources/policy/legislations/legislative-memo-empire-worker-protection-act.

Related to

Related Resources

All resourcesWhen ‘Bossware’ Manages Workers: A Policy Agenda to Stop Digital Surveillance and Automated-Decision-System Abuses

Report

Delivering Precarity: How Amazon Flex Harms Workers and What to Do About It

Policy & Data Brief

REI Workers Speak Out: Racial Discrimination, Inequity, and the Fight for a Fair Workplace

Report