This is part a four-part series that uncovers coerced labor in the U.S. and suggests pathways toward decarceration and worker power, emphasizing initial findings on labor protections in community service programs across states, with a focus on anti-Black criminalization and the undermining of labor standards.

Introduction

The twin expansions of fissured work and anti-Black criminalization over the last 60 years in the U.S. have contributed to the rise of workplaces directly created, managed, or brokered by the criminal legal system.

These include familiar examples such as prison labor, work release programs, and incarcerated emergency responders like wildland firefighters.

Less well known are parole and probation work mandates, court-ordered enrollment into programs that “rehabilitate” defendants through unpaid work, and, as we examine in this brief, unpaid, court-ordered community service work programs.

In all these cases, workers labor under the threat of incarceration if they are deemed noncompliant.1

Lawmakers, criminal legal system actors, and reformers alike often present community service work programs as an alternative to incarceration. Such work programs deserve much more scrutiny.

Through community service work programs, courts assign disproportionately Black and cash-poor workers to unpaid work in public and private workplaces under the threat of jail, reflecting larger, widely recognized structures of racism and classism in the criminal legal system.2

The direct extraction of unpaid work through anti-Black criminalization has a long and continuing history in the U.S. That extraction is one of the historical throughlines connecting chattel slavery to:

- “convict leasing” programs;

- postbellum Black codes and vagrancy laws;

- Jim Crow workplace segregation; and

- the current period of mass incarceration, so exacting in its remaking it has been famously dubbed the “New Jim Crow.”

In this context, forcing people to perform unpaid, unprotected work—or be thrown in jail—is no alternative at all, but instead a rebranding and expansion of criminalization into conventional workplaces.

Decarceral advocates have argued that, good intentions aside, purported alternatives to incarceration often wind up lengthening cycles of reincarceration, debt, and substandard work—expanding the reach of the criminal legal system even further into other spheres, namely the workplace and home.3

The language of “alternatives” can be especially alluring when the status quo is the largest system of incarceration in the world. The euphemism of “community service” itself suggests voluntary work, but such language obscures these work programs’ fundamentally coercive character, operating at the intersection of anti-Black criminalization and economic inequality.

This brief is the first installment in an ongoing project that strives to illuminate how coerced work in the U.S. endures and to chart an exit path toward both decarceration and worker power.

While today there are precious few labor protections in community service work programs across the U.S., the few that do exist can provide advocates some foundation to build broader challenges. In this brief, we highlight preliminary findings and analysis from a longer study examining labor protections and lack thereof in state statutes governing community service across the 50 states and the District of Columbia.4

A more developed and detailed analysis, including policy recommendations, is slated for publication later this year. We highlight which states include community service workers in at least some labor standards, which mitigate the fundamental coercion of working under the threat of jail, and which protect against displacement of other workers. Finally, we illustrate how community service work programs are best understood as low-road labor supply systems, expanding anti-Black criminalization into the workplace, lowering labor standards for all, and undermining workplace organizing.

Preliminary Findings

Community service work programs are ubiquitous. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have statutes authorizing them in at least some criminal cases, and 42 states authorize such work programs as a way to “work off” court-ordered debt.5

Criminalized workers are ordered to labor in both public and private workplaces and across many types of work, including nonprofits, data entry, warehousing, custodial services, food handling, park and roads maintenance, and landscaping—regularly assigning unpaid workers to work alongside regular employees.

The premise and purpose of community service programs is that people are working, in that they are engaging in activity that provides valuable services or products. But are they protected as workers? Or are they specifically excluded from such protections?

Without basic labor rights, community service programs are a recipe for exploitation, using the criminal legal system’s power to punish as a means to deliver a labor supply with minimal protection from labor law and maximum vulnerability through criminal law.

Below we highlight preliminary findings about where and how community service workers are protected in state laws governing court-ordered community service. More detail and finalized counts are forthcoming in our subsequent publication.

We organize this section around three potential areas of protection:

- General labor standards such as wage rates, workplace safety, and other protections

- Forced labor

- Displacement of other workers

“General labor standards” refers to protections characteristic of familiar labor and employment statutes that apply to typical paid workers. In U.S. law generally, this includes a wide range of topics like minimum wage, overtime, discrimination, family and medical leave, workplace safety, social insurance protections when unable to work, and rights to organize and bargain collectively. Workers considered “employees” generally receive all of these protections, though sometimes employee status varies with context, and some employers are exempt from coverage.6

We focus on wage rates and worker safety because existing community-service statutes address them most frequently. The absence of other protections is itself noteworthy.

Community Service Workers and Employee Status

Before getting into the details of specific labor standards, one can simply ask whether community service workers typically occupy the legal category of “employee.” If they do, various standard labor protections follow as a matter of course.

The most familiar disputes over employee status concern the distinction between employees and independent contractors, whereby employers shirk their duties like minimum wage and workplace safety standards by misclassifying workers as contractors. An employer’s control over how work is performed generally suffices to categorize a worker as an employee rather than an independent contractor.

For now, despite performing valuable work under another’s control, community service programs are generally structured on the assumption, even unstated, that any work assigned by the criminal legal system is excluded from employment protections.

Six states go further and expressly reject employee status by statute in at least some contexts, including situations where there is an explicit economic quid pro quo between work and credit towards fines and fees:

- Connecticut

- Hawai’i

- Illinois

- Kentucky

- New Mexico

- South Dakota

No state statute expressly includes community service workers as employees as a general matter. This question of employee status has rarely been examined in court.

One prominent California case did conclude that the quid pro quo of work for debt reduction counted as compensation that triggers employee status, and a federal judge in New York ruled that court-ordered community service was not employment when it lacked any direct financial exchange.7

Labor Standards: Wage Rates and Debt Conversion

Many states acknowledge the relevance of minimum wage standards to how community service work is valued, especially in the context of granting credit toward fines and fees based on an hourly rate. But using the minimum wage as a benchmark generally doesn’t mean treating the work as waged employment. Indeed, many of these states still explicitly treat the work as “unpaid” or specifically reject the notion that the work is entitled to wages, consistent with the more general rejection of employment status for community service workers.

States often authorize court-ordered community service in multiple contexts with rules that vary among them. For instance, some states only specify hourly credit rates toward debt from traffic court fines and fees and not toward criminal court debt arising from misdemeanor or felony convictions, or vice versa. Even where states frame community service as “working off” fines and fees at an hourly rate, some allow or even require courts to set rates below hourly minimum wage. Further, even where states explicitly acknowledge the significance of the minimum wage in determining conversion against debt, some of these states still permit courts discretion to set rates below hourly minimum wage. More detail will be forthcoming in our subsequent publication.

states explicitly tie credit against court debt to the federal hourly minimum wage in at least some contexts: Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, New Mexico, Ohio, and West Virginia.

states explicitly tie credit against court debt to their state’s hourly minimum wage in at least some contexts: Alaska, California, Iowa, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, Vermont, and Washington.

states explicitly set hourly rates at specific dollar amounts that fall below state and/or federal minimum wage in at least some contexts: Florida, Illinois, Kansas, and Massachusetts.

states explicitly state that community service work is “unpaid” in at least some contexts: Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

Labor Standards: Workers’ Compensation

Workers’ compensation laws generally cover medical expenses from a work-related injury or illness and provide wage replacement when such workplace harms leave workers medically unable to work or limited to work with lower earnings than before.

A unique feature of workers’ compensation laws is their double-edged character: worker benefits are part of a quid pro quo that also shields employers from tort liability for workplace injury or illness arising from their own negligence, essentially substituting a no-fault insurance regime. In that way, employers may actually benefit from employee status at the expense of workers, complicating the usual political calculus in which employers seek to deny the existence of an employment relationship in order to avoid legal duties to their workers.

Relatedly, state workers’ compensation laws often have considerably broader coverage than other employment laws. For instance, although courts generally exclude incarcerated workers from employment protections like minimum wage, even when there is no explicit statutory exclusion, incarcerated workers are occasionally included as “employees” for workers’ comp purposes.

Similar patterns apply to community service workers. Some states include community service in the employer liability shield component while denying workers access to compensation for the same injuries.

Again, we list states that do so for any form of court-ordered community service, even if not for all.

Three states wholly include community service workers as employees under their workers’ compensation laws: Florida, Idaho, and Nebraska.

Seven states explicitly include community service workers in some form of workers’ compensation but in a fashion separate from or less protective than the benefits for ordinary employees: Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Ohio, and Vermont.

Apart from exclusions from employee status generally, four states specifically exclude community service workers from their workers’ compensation scheme: Colorado, Kansas, Kentucky, and South Dakota.

Fourteen states explicitly shield community service employers from negligence liability for workplace injury while making no other provision for (or specifically barring) worker benefits: Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Labor Standards: Other Worker Protections

A handful of state court-ordered community service statutes address protections other than credit rates or work-related injuries.

- South Dakota explicitly excludes community service workers from unemployment insurance alongside workers’ compensation.

- Five states provide limited protections against overwork (e.g., breaks, maximum hours per day and/or week), albeit outside employment laws addressing overtime and break periods: Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Texas.

- No state provides any explicit protection against discrimination based on race, gender, disability, or other characteristics that may affect the position or type of work to which a community service worker is assigned—or the treatment that worker might face.

Forced Labor: Incarceration Threat

The threat of incarceration hangs over court-ordered community service. In 24 states a statute specifically authorizes revocation of probation (resulting in incarceration) for nonperformance of community service work.

Additionally, general court powers to enforce judgments include contempt that may result in incarceration for noncompliance with court-ordered community service, but the applicability of general court powers to community service is not generally spelled out in statute, so we do not attempt to document it here.

Twenty-seven states explicitly authorize revocation of probation (incarceration or reincarceration pursuant to the underlying conviction sentence) for noncompletion of community service in at least some contexts: Alaska, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Texas additionally authorizes a new, independent criminal charge for noncompletion of community service work, punishable up to two years and “not less than 180 days.”

Forced Labor: Alternatives to Work or Incarceration

Community service work is not the only structured activity outside of incarceration to which criminal defendants are sometimes sentenced, or the performance of which may be made a condition of probation or parole. Other common examples include education or training programs or drug rehabilitation.

In some circumstances, participation in such programs may itself be considered a form of “community service” or a substitute for it. Offering such alternative activities may provide affirmative benefits to participants and blunt the temptation to utilize the criminal legal system as a tool to deliver unpaid, vulnerable labor to employers. To be sure, the existence of such alternatives does not remove coercion from the system, and coercion into putatively beneficial services raises its own set of serious critiques.

Nonetheless, expanding the range of options creates pressures toward meaningful structures of care and mitigates the specific forms of labor subordination and extraction through involuntary servitude, which the 13th amendment recognizes as injustice of special importance.

From the perspective of avoiding forced labor, the crucial point is to avoid creating a stark choice between performing community service or being incarcerated. Offering a third possibility of some other activity that also satisfies the criminal legal system loosens this bind. Such choices are occasionally, though rarely, put in the hands of community service workers themselves. It is more common for sentencing judges to have the discretion to substitute such activities for community service.

New Jersey explicitly allows family counseling, drug treatment, and other services to satisfy obligations to “work off” court-ordered fines and fees.

states grant defendants discretion to choose an alternative activity in lieu of community service work in at least some contexts: Arizona, Florida, and Louisiana.

states grant discretion to the sentencing officer as to whether such alternatives can satisfy community service work obligations in at least some contexts: Arizona, California, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Texas.

Displacement: Limiting Impacts on Regular Employees

The vulnerability of community service workers gives employers an incentive to shift work away from paid employment toward community service work programs that permit employers to avoid wages, payroll taxes, and compliance with various workplace protections, as well as to wield power over workers for whom job loss could trigger incarceration. The loss of hours or positions in regular jobs from such a shift is called “displacement.”

In addition to protecting community service workers themselves, programs could be designed to prevent employers from using community service to undermine or displace other workers by performing work that would have otherwise been done by paid workers.

Such antidisplacement protections are a common feature of legal regimes governing other highly vulnerable workers—including ones sometimes lacking full labor protections themselves—such as migrant guestworker programs, prison labor, and welfare-to-work programs.8

A related protection allows community service workers to refuse to act as strikebreakers without subjection to penalties for refusing otherwise mandatory work.

- New York prohibits community service assignments that displace regular workers or at worksites where there is a labor dispute. No other state prohibits either.

Community Service Work Programs as Low-Road Labor Supply

The lack of worker protections in community service work programs suggests that they have received little scrutiny as low-road labor supply systems. Yet they bear many of the markings.9 These work programs supply targeted workers under conditions that give employers much greater power.

They impose far fewer protections against exploitation or abuse than when hiring employees through conventional labor markets. They sort and supply workers to a variety of third-party private and public workplaces. Workers often work alongside the third-party employer’s permanent, conventional workforce.

This results in a second-tier workforce who do the same or similar work as workers hired directly by the host employer, but for no pay, no benefits, and no job security.

Like temp and staffing agencies, community service work programs drive down the cost of wages and insulate workplaces from workers’ compensation, discrimination claims, and union drives, allowing workplaces to control working conditions without being responsible for them. As labor market intermediaries like temp and staffing agencies are increasingly the target of worker advocacy campaigns, decarceral advocates and worker advocates share an interest in both challenging criminal legal systems and organizing workplaces, together.10

Twin Expansions of Fissured Work and Anti-Black Criminalization

The domestic labor market has gradually shifted over the last 60 years or so, a history familiar to labor advocates. Long term, direct-hire jobs with employer-sponsored benefits and high unionization rates have declined. On the rise has been “fissured work”: shorter-term, increasingly precarious jobs with lower wages, fewer benefits, and more obstacles to collective action, all facilitated by schemes that allow economically powerful firms to obtain labor without taking on employer responsibilities.11

In addition to subcontracting or outsourcing, part of this history involves the rise of largely unregulated labor brokers like temp and staffing agencies who assign workers to private workplaces, often concentrated in underpaid industries that could not be wholly exported abroad like logistics, construction, and service work.

Labor brokers manage the hiring and paying of workers for third-party companies known as “host companies.” Brokers profit by charging the host employer a markup on hourly workers’ wages. Brokers compete with one another by driving down the cost of labor, the only cost they control, which incentivizes paying poverty wages and cutting corners on meaningful training and safety and health standards.

Brokered workers often work alongside a host employer’s permanent, conventional workforce, resulting in a second-tier workforce who do the same or similar work but for less pay, nearly nonexistent benefits, and no job security. Fissured work drives down wages and insulates host companies from workers’ compensation, Social Security and unemployment taxes, and union drives by attempting to establish the broker as the legal employer.

Over roughly the same period—in a history familiar to decarceral advocates—the U.S. increased its incarcerated population by 500 percent, to approximately 2.4 million people—crowning itself the world’s most incarcerated—under a sprawling system of punishment and surveillance that targets Black and Brown people.12

Through parole, probation, diversion, and similar programs, the criminal legal system further supervises and surveils an additional 3.9 million people under the threat of incarceration.13 One notable element of the expansion of criminalization has been the concurrent defunding of social service and welfare functions of government, highlighted especially by contemporary decarceral campaigns calling for divestment from punishment systems.14

Using the criminal legal system to supply labor has grave consequences. On an immediate level, the threat of incarceration chills speaking up at work against rights violations like safety hazards, discrimination, or harassment. That threat can stop a worker from asking for accommodations or organizing with their coworkers. Court-ordered community service work programs supply workers in conditions below even the substandard conditions that temp and staffing agencies do.

Community service work programs:

- Operate below basic worker protections characteristic of labor and employment statutes;

- Coerce individuals targeted by criminalization into unpaid, extractive work at the threat of incarceration; and

- Displace and discipline regularly compensated employees.

Court-ordered community service has significance for community service workers above and beyond the immediate labor conditions they experience. Community service work programs also pressure their workers to accept bad jobs in the conventional labor market.

Similar to how unpaid or barely paid incarcerated work makes postrelease, underpaid work look good by comparison—“After years of working for pennies on the dollar inside, twelve dollars an hour sounds great to someone coming out of prison, even if you could never make the costs of living in New York City with that pay.”15—unpaid community service work trains workers to expect less in pay, benefits, safety, and bodily autonomy from the job market.

This downward pressure on labor markets is particularly clear when court-ordered community service is imposed on those financially unable to pay fines and fees. When the criminal legal system narrows the practical alternatives to either incarceration for nonpayment or unpaid, unprotected community service to work off court debt, pursuing payment through even the worst paid jobs at the bottom of the labor market become more attractive in comparison—even for those who might otherwise find ways to survive by other means.

In this fashion, community service work provides a new iteration in the criminal legal context of familiar “workfare” schemes (work assignments as a condition of receiving public assistance to meet basic needs) that simultaneously extracted labor through unpaid, unprotected work and, by subjecting people to those conditions, pushed them into the bottom of the labor market.16

By subjecting people within institutions of racialized poverty management to living and working conditions below the ordinary conditions of work in low-paid (which are really underpaid) labor markets, state institutions validate those markets and drive people into them.

When employers make use of community service workers in a workplace, conventional employees are also impacted. However differently labor is recruited and disciplined, community service workers are producing valuable products and services that might otherwise be the jobs of paid and protected workers. Historically, this basic point provided the foundation for labor movement mobilization and anti-displacement provisions of varying strengths against abusive penal labor programs in prisons, chain gangs, and convict leasing schemes.

The threat of such displacement also may discipline workers into moderating their demands or accepting concessions. That disciplinary function against workers collectively also operates at the level of individual workers: community service work programs convey to all workers at a worksite, including conventional employees, that they ought to be grateful they are not incarcerated, working down a court debt, or denied stable work or promotion for being marked by a record—consequences they might personally face if they pass up the limited jobs available to them in our unequal labor market.17

At the level of policy debate, the existence of court-ordered community service as a solution to unpayable, state-imposed debt, especially one that provides an “alternative to incarceration,” insulates the underpaid labor market from critique and reconstruction.

In other words, the reason why “inability to pay” is pervasive among Black and Brown people targeted by criminalization is precisely wholesale exclusion from access to decent jobs and incomes. Or to put it positively, creating an equitable, good jobs economy would also address the “ability to pay” problem, rather than pursuing the lowest of low-road solutions through community service—which operate below even the nominal “floor” of existing labor standards. Similarly, for decarceral advocates, removing the community service “alternative” from the menu complements efforts to scale back underlying practices of criminalization and imposition of fines and fees, rather than legitimating them through promotion of community service work programs.

Purported alternatives like community service can crowd out deeper, structural propositions like building the solidarity and bases of support between labor and decarceral movements necessary for creating a horizon of an equitable, good jobs economy for all.

Horizons

While today there are precious few labor protections in community service work programs across the U.S., the few that do exist can provide advocates with some foundation on which to build broader challenges.

Our recommendations will be elaborated and detailed in a publication slated for later this year, but, simply put, the criminal legal system should not create a parallel, substandard labor structure that targets the very people and communities already most subjected to carceral state violence and most excluded from economic stability and opportunity.

Policy should not merely mitigate the worst forms of exploitation and abuse but should instead chart a course toward both decarceration and economic justice. For the purposes of this initial brief, we offer a vision for four complementary paths of change:18

- Raising labor standards for any court-ordered community service toward parity with conventional employment;

- Prohibiting employers from using community service workers to displace conventional employees (or threatening to do so);

- Utilizing job creation techniques to provide affirmative access to fully protected jobs for anyone unable to pay fines and fees due to un(der)employment; and

- Removing carceral labor coercion by creating options to fulfill payment or labor obligations through productive activities not involving labor extraction.

Ultimately, broad and pluralistic workers’ and social movements must be built and grown, not just individual policies won. When decarceral and labor movements organize together to overcome a punishment system that subordinates and exploits labor, we advance toward structural transformation.

Policy campaigns can simultaneously serve two purposes: immediate relief for some and the means to advance deeper challenges against anti-Black punishment, structural inequality, and coerced labor, in favor of an economy where good jobs are available to all who want them.

Related to

- Elsewhere, we have called this threat of state violence through criminal punishment at work “structures of worker criminalization” and the “carceral labor continuum.” Noah Zatz, “The Carceral Labor Continuum,” Inquest, June 1, 2023, https://inquest.org/the-carceral-labor-continuum; Han Lu, Worker Power in the Carceral State (New York: National Employment Law Project, 2022), https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Worker-Power-in-the-Carceral-State-10-Proposals.pdf.

- Racialized targeting and inequality in the criminal legal system is widely recognized and occurs through a variety of policing and prosecutorial strategies such as geographically concentrated racial profiling, prosecutorial bias, insufficient indigent defense funding, and sentencing discrimination. In New York, home to NELP headquarters, Black people comprise 15 percent of the population, 43 percent of the jail population, and 48 percent of the prison population. See, e.g., Incarceration Trends in New York (New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2019), https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-new-york.pdf. See also, “Most Judges Believe the Criminal Justice System Suffers from Racism,” National Judicial College, July 14, 2020, https://www.judges.org/new-and-info/most-judges-believe-the-criminal-justice-system-suffers-from-racism.

- On the carceral effects of “alternatives to incarceration,” see Maya Schenwar and Victoria Law, Prison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular Reforms (New York: New Press, 2021). On probation and parole supervision programs as “recidivism traps,” see Vincent Schiraldi, Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom (New York: New Press, 2023).

- The baseline survey of community service statutes is as of 2021. The labor-related provisions central to this brief were systematically updated as of 2022, with subsequent changes noted where they have come to our attention.

- Lucero Herrera et al., Work, Pay, or Go to Jail: Court-Ordered Community Service in Los Angeles (Los Angeles: UCLA Labor Center, 2019), https://www.labor.ucla.edu/publication/communityservice.

- For examples on discriminatory exclusions from employment protections, see, e.g., Rebecca Dixon, “Fair Labor Standards Act: After 85 Years, Still Working Toward Justice for All,” National Employment Law Project, June 2023, https://www.nelp.org/fair-labor-standards-act-after-85-years-still-working-toward-justice-for-all/.

- Arriaga v. County of Alameda, 892 P.2d 150 (Cal. 1995); Doyle v. City of New York, 91 F. Supp. 3d 480 (S.D.N.Y. 2015).

- By comparison, antidisplacement provisions are common even in prison labor programs, where incarcerated workers are subjected to high levels of coercion and exploitation with almost no protections for their own working conditions or recognition of their labor’s value. But an extensive set of state and federal statutes are designed to prevent exploitation of incarcerated workers as substitutes for employees in the “free world.” Zatz, “Carceral Labor Continuum.” Similarly, even when the 1996 federal welfare reform law repealed many previous labor protections for workfare workers, it retained nationwide protections against displacement. 42 U.S.C. § 607(f).

- Herrera et al., Work, Pay, or Go to Jail.

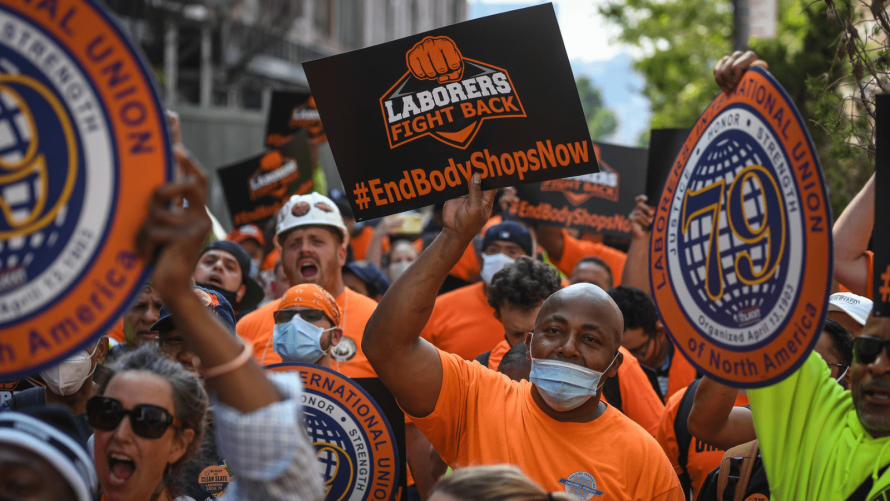

- Concerned with how court-supervised workers were both being exploited and being leveraged against unionized workers, New York’s Construction and General Building Laborers’ Local 79 organized its “Real Reentry” campaign, targeting labor brokers and developers in the construction industry. Their victories included legislation requiring labor brokers in New York City to maintain insurance for workers’ compensation, disability, and unemployment, and, importantly, changes to parole rules that previously could have treated workplace organizing as a parole violation. Han Lu and Bernard Callegari, “Building Anti-Carceral Unionism: A Q&A on Local 79’s ‘Real Reentry’ Campaign,” Law and Political Economy Blog, https://lpeproject.org/blog/building-anti-carceral-unionism-a-qa-on-local-79s-real-re-entry-campaign/; Real Re-Entry website, https://www.realreentry.org. On building bases of solidarity between prison abolitionists and labor advocates, see Zatz, “Carceral Labor Continuum.” On temp worker organizing generally, see Temp Worker Justice website, https://tempworkerjustice.org.

- Laura Padin, Eliminating Structural Drivers of Temping Out: Reforming Laws and Programs to Cultivate Stable and Secure Jobs (New York: National Employment Law Project, March 2020), https://www.nelp.org/publication/eliminating-structural-drivers-temping-reforming-laws-programs-cultivate-stable-secure-jobs/; On the “fissured workplace,” see, e.g., David Weil, The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What can be Done (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

- Class and race disparities are structured into an ostensibly “class-blind” and “color-blind” criminal law. In practice, this willful “blindness” permits criminal law institutions to reflect, intensify, and generate additional forms of class and race inequalities in the larger economy. See, e.g., Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System (Washington, DC: Sentencing Project, 2018), https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities.

- Probation and Parole in the United States, 2020 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2021), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus20_sum.pdf.

- For a history of the transformation of governance from welfare to racialized punishment over the past 50 years, see, e.g., Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017); Loïc Wacquant, Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity (Durham, Duke University Press, 2009). Contemporary and overlapping social movements with roots in Black feminist organizing, queer organizing, and abolitionist organizing have repeatedly challenged inflated and overfunded municipal, state, and federal budgets that expand punishment and surveillance and that deepen racialized economic inequality. See, e.g., Money for Communities, Not Cages: The Case for Reducing the Cook County Sheriff’s Jail Budget (Chicago Community Bond Fund, 2018), https://chicagobond.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/money-for-communities-not-cages-why-cook-county-should-reduce-the-sheriffs-bloated-jail-budget.pdf; “Section 1: Divesting Federal Resources from Incarceration and Policing and Ending Criminal Legal System Harms,” The Breathe Act Proposal (Mobilization for Black Lives, 2020) https://breatheact.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/The-BREATHE-Act-V.16_.pdf.

- Bernard Callegari, lead organizer and member of Laborers Local 79 Fight Back Campaign.

- Chad Alan Goldberg, Citizens and Paupers: Relief, Rights, and Race from the Freedmen’s Bureau to Workfare (University of Chicago Press, 2007); Jane L. Collins and Victoria Mayer, Both Hands Tied: Welfare Reform and the Race to the Bottom in the Low-Wage Labor Market (University of Chicago Press,) 2010.

- Noah D. Zatz, “Better Than Jail: Social Policy in the Shadow of Racialized Mass Incarceration,” Journal of Law and Political Economy 1, no. 2 (2021): 212, https://escholarship.org/content/qt38q093rd/qt38q093rd.pdf.

- Herrera et al., Work, Pay, or Go to Jail.