State legislatures around the country are attempting to bar cities and counties from passing their own minimum wage laws through “preemption” laws that take away a local government’s power to enact such measures. These preemption laws form part of a bigger trend of state legislatures preventing local governments from passing local solutions aiming to address pressing public health needs, environmental concerns, a desire for good jobs, and more.

Local minimum wage laws play a key role in ensuring that a worker can afford the basics in cities or counties where the cost of living is higher than in other parts of the state. Montgomery County and Prince George’s County have adopted local minimum wage laws higher than the state minimum wage and shown how local governments can do this successfully.

State legislators should support local communities that want to build upon the state’s minimum wage to address their particular needs and reject any effort to preempt local minimum wage laws.

Many States Authorize Cities & Counties to Enact Local Minimum Wage Laws; Over 40 Cities & Counties Have Successfully Enacted Such Laws

- Many states, cities, and counties have the power to adopt local minimum wage laws that provide for a higher minimum wage than state or federal law.

- In Maryland, Montgomery County approved its first $11.50 minimum wage law in 2013.[i] In 2017, the county approved another gradual minimum wage increase to $15 per hour.[ii] In 2013, Prince George’s County also approved a minimum wage increase to $11.50 by 2017.[iii]

- Across the country, more than 40 cities or counties in states such as California, New Mexico, and Arizona have adopted local minimum wage laws that have successfully helped workers better afford the basics.[iv]

- Local minimum wage laws—which generally impact just a few high-cost communities in a particular state—have proven effective and manageable for businesses.

- The most recent study of city-level minimum wage increases released in 2018 documents the negligible impact of raising the minimum wage in six cities: Chicago, the District of Columbia, Oakland, San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle.[v] It is also the first study to examine the effects of increasing the minimum wage above $10.[vi] The study concluded that “a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage increases earnings in the food services industry between 1.3 and 2.5 percent” without a discernible negative impact on employment.[vii]

- A recent op-ed by Chicago’s Deputy Mayor and the Commissioner of the Chicago Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection put the impact of Chicago’s minimum wage in these terms: “In Chicago, wages are up and unemployment is down. . . . When Chicago passed our ordinance raising the wage, there were plenty of voices in the business community who seemed certain the sky would fall. . . . These concerns were based in mythology, not reality.”[viii]

- The economic evidence also shows that a city or county that adopts a higher local minimum wage does not become “less competitive” with surrounding areas, another frequent claim by proponents of preemption. One of the most sophisticated studies of minimum wages was published by economists at the Universities of California, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.[ix] The study looked at the impact of minimum wage rates in more than 250 pairs of neighboring counties in the United States that had different minimum wage rates.[x] Comparing neighboring counties on either side of a state line is an especially effective way of isolating the true impact of minimum wage differences, because neighboring counties tend to have similar economic conditions. The study found no difference in job growth rates.[xi]

Local Power to Raise the Minimum Wage Is Important for High-Cost-of-Living Communities

- Local power to raise the minimum wage allows higher-cost-of-living communities in a state to adopt wages that better match their higher housing and living costs.

- A U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics analysis found that urban households in 2011 spent 18 percent more than rural households, and higher housing costs by urban consumers “accounted for about two-thirds of the difference in overall spending between urban and rural households.”[xii]

- Nowhere in Maryland is less than $15 per hour enough to sustain a single adult without children. However, the cost of living can still vary significantly across cities and counties. For example, the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator estimates that a single worker in Prince George’s County needs at least $21 per hour working full-time to make ends meet (in 2017 dollars). The same single worker working full-time in rural Garrett County would need about $16 per year to make ends meet.[xiii]

Maryland Lawmakers Should Reject Preemption and Protect Cities’ and Counties’ Ability to Build Upon The Statewide Minimum Wage

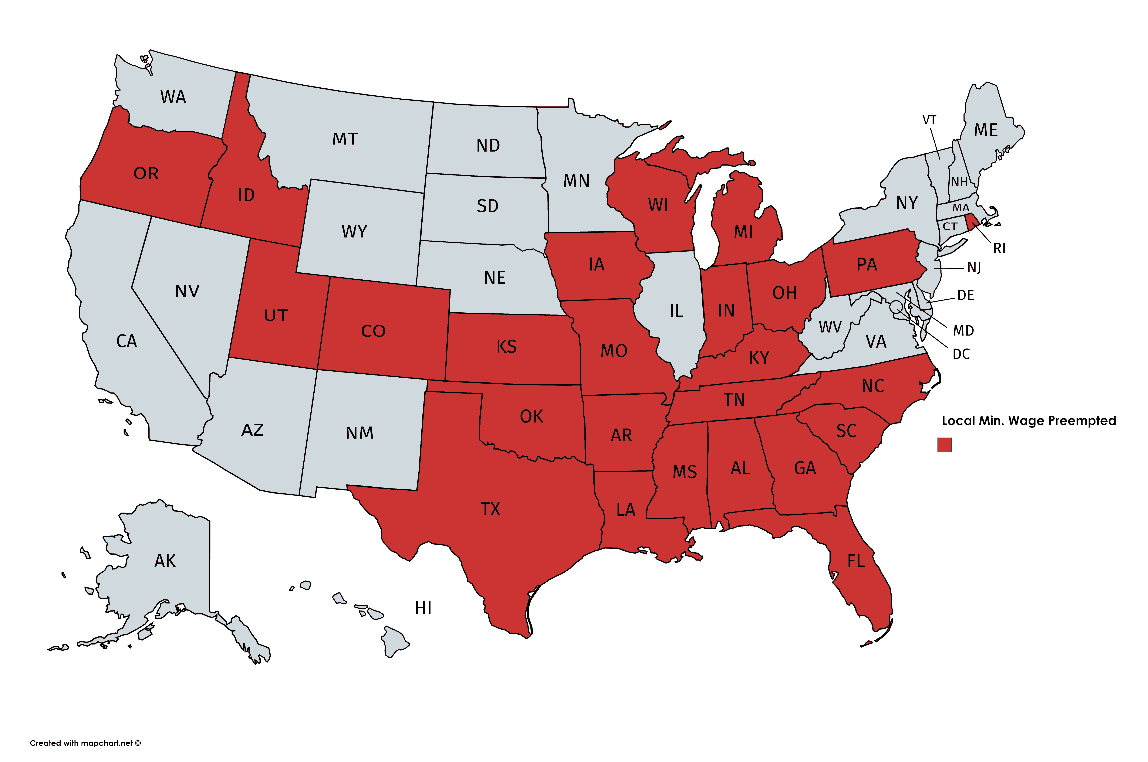

- As of the date of this publication, 25 states have passed laws that preempt cities from passing their own local minimum wage laws.[xiv] See Figure for a map of states that have passed minimum wage preemption laws.

- Most state preemption laws have been passed in recent years as a response to successful local campaigns to raise the minimum wage.[xv] In 2016, for example, the State of Alabama passed a preemption bill after the City of Birmingham passed a local minimum wage law.[xvi] The effect was not only to block future local minimum wages, but to invalidate Birmingham’s higher minimum wage law.

- While proponents of preemption often claim they are concerned about having a “patchwork” of wage levels across the state, businesses are accustomed to dealing with varying rules across cities and counties. Cities in most of the country have extensive “home rule” powers allowing them to legislate over a wide range of areas in order to adequately respond to local needs. Businesses have adapted to varying rules concerning traffic, business licenses, construction, zoning, and many other local laws. Local minimum wages are no different.

- Taking away local control over wages has become a major priority of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a special interest group with extensive lobbying resources and influence in our state legislatures.

- As a Slate article explained, “[f]ounded in 1973, [ALEC] has paired lawmakers with businesses and special interests ranging from Google to the AARP to Exxon Mobil” to produce “hundreds of ‘model policies’ that have made their way into state codes.”[xvii] ALEC has successfully preempted local laws on a growing list of important issues like guns, tobacco, wages, the banning of plastic bags, fracking, and pesticides.[xviii]

- ALEC has drafted “model” preemption bills to prohibit local minimum wage laws since at least 2002.[xix]

Figure: States That Have Adopted Minimum Wage Preemption Laws

(as of January 31, 2019)

Voters Across the Country Believe That Their Local Governments Should Be Able to Adopt Policies That Reflect Local Values

- Across the country, voters across party lines believe that local governments are well-positioned to craft and adopt policies that correspond to local needs.

- In Maryland, while the state legislature plays a key role in setting minimum standards, state lawmakers should continue to protect cities’ and counties’ ability to adopt a higher local minimum wage that meets their particular needs.

- A national poll found that 58 percent of voters believe that state legislatures “threaten local democracy and silence the voices of the people” when they pass preemption laws or strike down local ordinances.[xx]

Conclusion

Maryland advocates, workers, and legislators must reject efforts to take away Maryland cities’ and counties’ existing authority to adopt a higher local minimum wage. Workers in high-cost cities and counties face especially difficult economic challenges due to a higher cost of living, and local governments must be able to respond to the unique needs of workers who cannot survive on the federal or state minimum wage.

Download the publication below.

[i]. Bill Turque, “Montgomery Council votes to increase minimum wage,” The Washington Post, Nov. 26, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/maryland-news/montgomery-council-votes-to-increase-minimum-wage/2013/11/26/ecc295c2-56ee-11e3-ba82-16ed03681809_story.html?utm_term=.748079dc2001.

[ii]. Rachel Siegel, “Montgomery County’s $15 minimum wage bill signed into law,” The Washington Post, Nov. 13, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/md-politics/montgomery-countys-15-minimum-wage-bill-signed-into-law/2017/11/13/d18ec0f4-c87e-11e7-b0cf-7689a9f2d84e_story.html?utm_term=.db7b88e0f0c0.

[iii]. Brad Bell, “Minimum wage increased [sic] enacted in Prince George’s, approved in D.C.,” WJLA, Dec. 17, 2013, http://wjla.com/news/local/prince-george-s-county-to-sign-minimum-wage-bill-98206.

[iv]. See National Employment Law Project, Impact of the Fight for $15: $68 Billion in Raises, 22 Million Workers (Nov. 2018), https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/Data-Brief-Impact-Fight-for-15-2018.pdf.

[v]. Sylvia Allegretto et al., Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics, The New Wave of Local Minimum Wage Policies: Evidence from Six Cities (Sept. 6, 2018), http://irle.berkeley.edu/the-new-wave-of-local-minimum-wage-policies-evidence-from-six-cities/.

[vi]. Id. at 2.

[vii]. Id.

[viii]. Robert Rivkin and Rosa Escareno, “Here’s what Chicago’s higher minimum wage really did,” Crain’s Chicago Business, July 26, 2018, http://www.chicagobusiness.com/node/811556/printable/print.

[ix]. Arindrajit Dube et al., The Review of Economics and Statistics, Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties (Nov. 2010) at 92(4): 945–964.

[x]. Id.

[xi]. Id.

[xii]. William Hawk, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Beyond the Numbers, Expenditures of urban and rural households in 2011 (Feb. 2013), https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-2/pdf/expenditures-of-urban-and-rural-households-in-2011.pdf.

[xiii]. Economic Policy Institute, Family Budget Calculator, https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/.

[xiv]. National Employment Law Project analysis of state laws. The Florida legislature enacted statewide legislation to preempt local minimum wage laws, but the validity of that laws is currently being challenged in court based on the language of a constitutional amendment approved by voters. City of Miami Beach v. Florida Retail Federation, Inc. et al. (Fl. Sup. Ct., filed Dec. 27, 2017) (No. SC17-2284).

[xv]. Of the 25 states identified in the Figure as having passed a minimum wage preemption law, more than half (14) adopted their minimum wage preemption law in or after 2013. See Ala. Code § 25-7-41; Idaho Code Ann. § 44-1502; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 12-16, 131; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 12-16, 130; HB3, 2016 Reg. Sess. (KY. 2017); Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 123.1395; Miss. Code Ann. § 17-1-51; Mo. Ann. Stat. § 285.055; N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 95-25.1; SB331, 131st Gen. Assem. (OH. 2016); Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 40, § 160; R.I. Gen. Laws Ann. § 28-12-25; Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-2-112; HF295, 87th Gen. Assem. (IA. 2017); SB668, 91st Gen. Assem. (AR. 2017). All 25 states enacted their minimum wage preemption laws in or after 1999. National Employment Law Project analysis of state laws.

[xvi]. Mike Cason, “Gov. Robert Bentley signs bill to block city minimum wages, voiding Birmingham ordinance,” AL.com, Feb. 25, 2016, http://www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2016/02/bill_to_block_city_minimum_wag_2.html.

[xvii]. Henry Grabar, “The Shackling of the American City,” Slate, Sept. 9, 2016, http://www.slate.com/articles/business/metropolis/2016/09/how_alec_acce_and_pre_emptions_laws_are_gutting_the_powers_of_american_cities.html.

[xviii]. Id.; Brendan Fischer, The Center for Media and Democracy’s PRWatch, Corporate Interests Take Aim at Local Democracy (Feb. 3, 2016), http://www.prwatch.org/news/2016/02/13029/2016-ALEC-local-control.

[xix]. American Legislative Exchange Council, Living Wage Mandate Preemption Act, https://www.alec.org/model-policy/living-wage-mandate-preemption-act/ (last viewed Jan. 31, 2019).

[xx]. Anzalone Liszt Grove Research, Preemption National Survey: Findings and Recommendations from a Nationwide Online Survey (Jan. 2018).