Unemployment Insurance (UI) is a critical earned benefit for workers who find themselves involuntarily unemployed. The UI program was designed to achieve several important objectives: provide income protection when circumstances outside workers’ control leave them without work; help people remain attached to the workforce through work-search guidance and assistance; and help prevent salary erosion and downward pressure on the value of labor by giving workers support for a time period long enough to find employment that is a suitable replacement for their lost job. UI’s countercyclical structure allows states to set aside funds when unemployment is low so that benefits sufficient to maintain spending and foster recovery can be paid when the economy falters.

The combination of changes that North Carolina made to its program in 2013 has left the program on shaky ground, ill-equipped to achieve these objectives. NELP recommends revisiting these changes now that the program is in a comfortable position in terms of solvency to pay out benefits due. To restore the state UI program’s ability to adequately support claimants and sustain the state’s economy through a future downturn, NELP recommends revisiting the changes enacted by the legislature in 2013, particularly now that the program is in a stable solvency position.

Duration of UI Benefits

North Carolina is one of 10 states that reduced the maximum duration of benefits from what was previously the standard of 26 weeks. The UI legislation passed in 2013 reduced maximum benefit duration from 26 weeks down to a range of 12 to 20 weeks, depending on the unemployment rate. The unemployment rate required to hit the 20-week maximum is an astoundingly high 9 percent; an unemployment rate below 5.5 percent triggers the 12-week maximum duration.

Even the 20-week maximum duration fails to cover the average duration of a typical worker’s period of unemployment—about 21.4 weeks nationally. The reduced benefit duration also disproportionately affects workers of color, who experience longer periods of unemployment. Black workers’ average duration of unemployment is 24 weeks nationally, while for Asian workers it is 23.4 weeks.[1]

Changes that North Carolina made to its UI program in 2013 have left it on shaky ground.

The sharply truncated UI benefit durations in North Carolina have compound negative effects on workers. They force workers to accept lower-paying jobs and jobs that are a worse fit for their skills and experience. This not only drives down wages but can result in shorter periods of subsequent employment as well. This effect is exacerbated by the fact that the 2013 law also changed the pay-level standard for a “suitable replacement” job—one that would require a claimant to accept a job offer or lose benefits. Now, if a job offers just 50 percent more than a worker receives in UI benefits, even if that job is part time, the worker would have to accept the offer.

The reduction in benefit durations also limits the available support from federal UI extensions during economic downturns. Historically, there are two ways that UI benefits can be extended during recessions. One is an automatic extension included in federal law called Extended Benefits (EB). Although colloquially thought to provide a uniform 13 weeks, EB can actually provide up to 20 weeks, or 80 percent of the total state benefits, depending in part on that state’s unemployment rate. The second way requires Congressional action. In fact, Congress has regularly enacted further supplemental extensions during recessions, such as the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program in the most recent recession.

In a future economic downturn, the average North Carolinian would receive up to $24,381 less in UI benefits because of the state’s reduced benefit duration alone.

Because federal extensions are based on existing state UI benefit durations, states that reduce UI durations lose out on weeks of federally funded benefits at a time when the state economy is most in need of a boost. Economists Alan Blinder and Mark Zandi examined all stimulus expenditures during the peak of the last recession and found that UI benefits had some of the most positive local economic impacts. They found that each dollar paid in UI produced $1.61 in local economic activity. North Carolina would stand to lose out on that multiplier several times over as a result of its shortened benefit durations. The U.S. Government Accountability Office looked at how much unemployed workers would have receive had they entered the last recession with the reduced duration of benefits and found that an average North Carolinian who was eligible for all of the UI extensions would have received between $21,973 and $24,381 less over their period of unemployment.

Sufficiency of UI Benefits

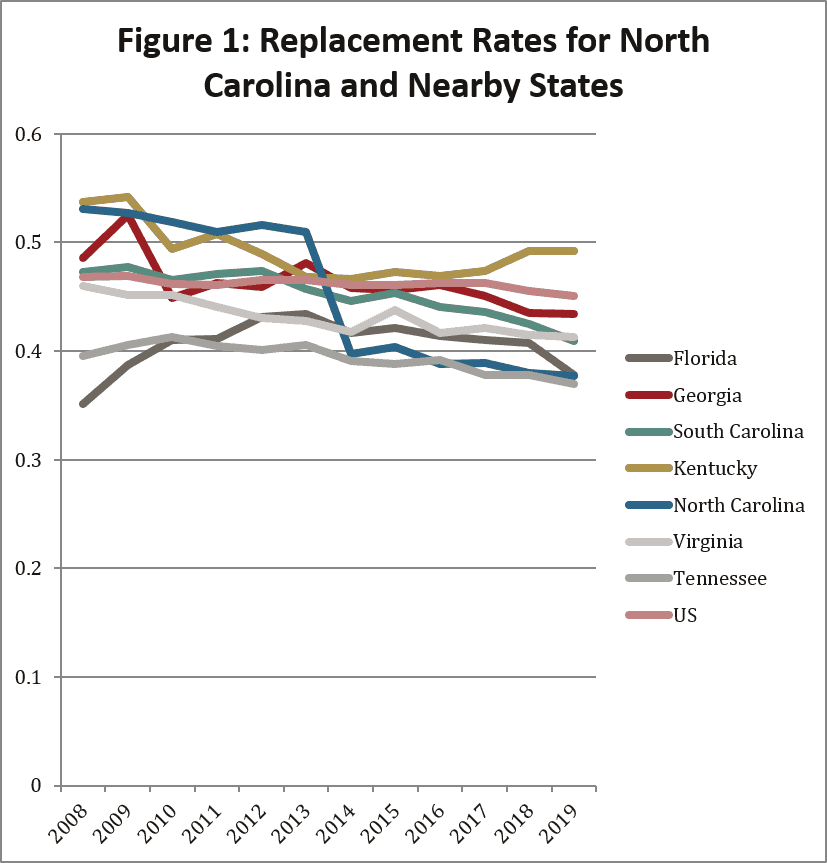

Experts recommend that in order to be meaningful, a UI benefit should replace half of an average worker’s weekly wages. Before the last recession, in 2007, North Carolina’s “replacement rate” was 49 percent.[2] That dropped to 38 percent in 2019. (See Figure 1.) Included in the 2013 legislation was a shift to calculating the weekly benefit amount on earnings in the most recent two quarters, or six months of work, rather than on the highest quarter of earnings in the benefit base period. This change effectively cuts benefits in two ways. First, averaging two quarters instead of simply using the highest quarter will usually result in a smaller benefit amount. Second, making it the most recent two quarters instead of the highest quarter can be particularly detrimental for a worker in a job that had cut back available hours and pay if it experienced a business slowdown. The change in the benefit-amount calculation can also harm workers in industries with highly variable hours and pay when they become unemployed.

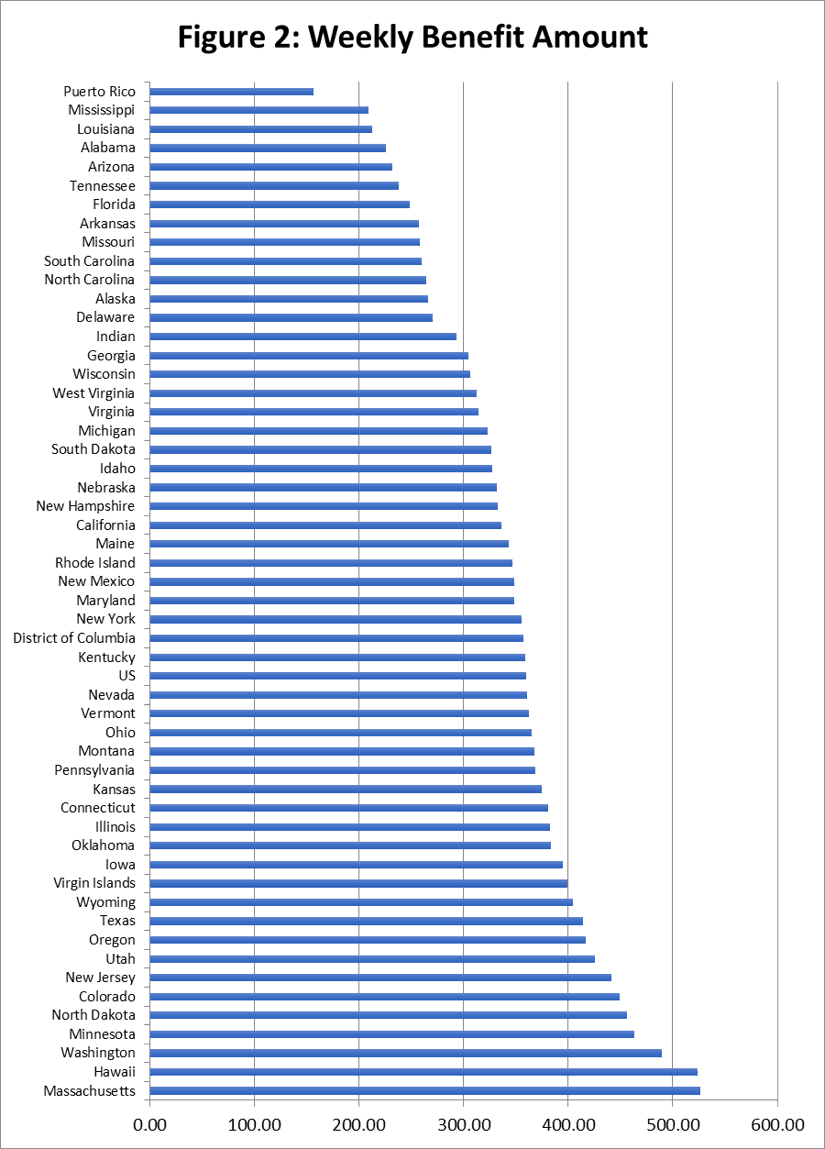

The 2013 change in the method for calculating benefit amounts caused a decline in the share of prior earnings being replaced for claimants, as well as a correlated decline in the average weekly benefit paid to claimants. In North Carolina, the average weekly benefit was $264.70 in the third quarter of 2019. Here is how that stacks up with other states, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment and Training Administration. (See Figure 2, on following page.)

NELP recommends that the state restore the calculation method it used prior to 2013, basing weekly benefit amounts on the highest quarter of earnings.

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration

UI Recipiency

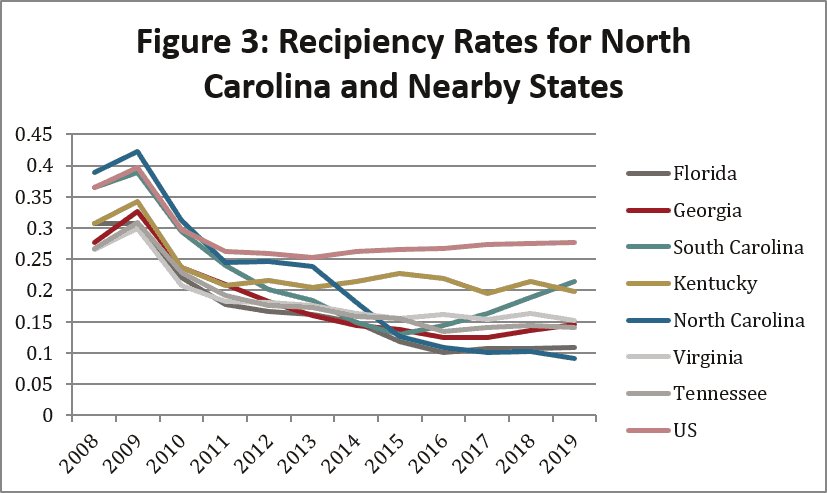

Recipiency is a measure of the share of unemployed workers receiving unemployment benefits. Historically, this number hovered around 50 percent. Clearly, not all workers who are out of work will qualify for UI for a variety of reasons. Some have exhausted their benefits; some left work for reasons that do not qualify them for UI; some may have no need or inclination to seek work; others choose not to file for UI for some reason. Overall, the recipiency rate has been declining nationwide, but it has slowly ticked up a bit in the past couple of years.

North Carolina’s recipiency rate has plummeted and is now the lowest in the United States. It was 9.1 percent for 2019, dropping as low as 8.3 percent in the third quarter. (See Figure 3.)

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration

Many factors can affect a state’s recipiency rate. For North Carolina, one significant factor is called the “exhaustion rate,” which is the share of UI recipients who run out of benefits before becoming reemployed. At 47.1 percent, North Carolina’s exhaustion rate is second highest in the nation.

Several other changes enacted in 2013 also contribute to North Carolina’s low recipiency rate. For example, the new law increased the waiting period in certain circumstances to receive a benefit. Many states have a waiting week—frankly a relic from an earlier time—but no other state has more than one waiting week in the case where a worker files more than one claim in a year. The law also removed qualifying good-cause reasons for leaving a job, including family caregiving or leaving because a closure is pending, or to follow a spouse who has to relocate for work. It is also harder now for workers whose hours are reduced to qualify for benefits.

Other causes of declines in recipiency relate to new online computer systems that are more difficult for workers to navigate or that may increase improper denials or inaccurately flag workers for fraud. Out of necessity, the state shifted to a new system from an antiquated one. But pre-rollout testing may have been less than rigorous. Many claimants reportedly had great difficulty accessing benefits due to system errors soon after the agency rolled out the new platform. It is still unclear whether system errors have been resolved; but to the extent that improper denials have increased, the state should take immediate action to make sure claimants are well-served by the new technology. NELP recommends that the state convene a working group of users to make sure that the new system is user-friendly for the people who need to use it.

Finally, there is an important connection between UI recipiency and workforce training and employment services. A key feature of the unemployment system is that it helps keep workers attached to the workforce. To help unemployed workers get back to work in good jobs, it is critical to provide direct assistance that helps workers focus their job searches and ensures they continue to meet UI eligibility requirements. A UI benefit brings with it a connection to an entire range of work-search and job-training opportunities. Workers can use periods of unemployment to improve their skills through training, and employers can benefit from a better-trained workforce. And the whole community benefits when there is less downward pressure on wages overall. Currently, there is broad bipartisan commitment to support additional funding for Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessment (RESEA) efforts. Studies have shown that when agency staff are well training in UI and reemployment services, these efforts reduce duration of unemployment and yield greater subsequent longevity at workers’ next jobs. North Carolina’s economy is losing out on all these benefits with its record-low access to the UI system.

UI Trust Fund Solvency

One measure of recession readiness is UI trust fund solvency. But the solvency level matters far less if the program is not paying benefits sufficient for workers to maintain spending power in a downturn. North Carolina’s trust fund is in good shape compared to past levels and compared to other states. This means that the system has the funds to pay appropriate benefits. Again, if benefits provide insufficient buying power, are available to too few people, and for durations that are just too short, a flush trust fund does not signify a recession-ready system. It would be far wiser for the state to expand benefits before it is too late—before the next downturn—to make sure these funds do what they are supposed to do in any upcoming recession. Figure 4, on the last page of this document, illustrates North Carolina’s solvency level compared to all other states.

Overall Recession Readiness & Recommendations

Although its trust fund is in good shape, North Carolina’s unemployment insurance is ill-prepared for another recession. Too few unemployed people receive benefits, and the benefits they get are not sufficient to replace enough income to maintain the level of buying power needed to sustain the local economy. Taken together with other changes that will depress workers’ ability to find good replacement work, this system will keep North Carolina’s economy in a downturn longer than other states that have not gutted UI benefits in the same extreme manner.

In order to prepare its UI program to be responsive to a potential future downturn, North Carolina lawmakers should immediately reverse several provisions of the 2013 legislation:

- Duration should be restored to 26 weeks;

- Benefits should be based on the highest quarter of earnings;

- Waiting weeks should be eliminated, or at least reduced to a maximum of one week;

- The maximum benefit should be increased to at least $400 per week and indexed to 40 percent of the state’s average weekly wage;

- Good-cause quits should be restored to pre-2013 definitions; and

- The pay level constituting suitable work should be commensurate with the workers’ pre-unemployment pay rate.

Download the full policy brief to read more.